Five Iconic Illustrators Who Transformed Children's Books Forever

Meet the illustrators whose distinctive styles helped shape the golden age of children’s books — turning simple stories into unforgettable visual experiences.

Five Iconic Illustrators Who Transformed Children's Books Forever

In celebration of International Children’s Day (1 June), we are spotlighting five visionary illustrators who transformed children’s books through their unforgettable art. These iconic creators redefined how generations of children visualised stories — and their legacy continues to influence readers, artists, and collectors alike. Whether you’re a lifelong fan or an avid rare book collector, explore the illustrators whose distinctive visual styles shaped the genre and left a lasting mark on children’s books.

Arthur Rackham

Arthur Rackham (1867–1939) is widely regarded as one of the most influential of children’s book illustrators. His name is synonymous with the Golden Age of illustration. Born in London, Rackham’s early years were marked by a passion for drawing, which he nurtured while juggling work as an insurance clerk and studies at Lambeth School of Art. His first attempts at illustration appeared in London newspapers and guidebooks, but it was his breakthrough with the colour plates for the tales of the Brothers Grimm that propelled him into the public eye.

In his illustrations, Rackham showcased his mastery of pen and ink combined with delicate watercolour washes, a style that blended Northern European folklore, Japanese woodblock tradition, and a touch of the grotesque, creating a dream-like atmosphere that captivated both children and adults. His intricate drawings for Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, first published in 1906, further cemented his reputation as a master of his craft.

Rackham’s works were a response to the unstable and rapid changes of his era. Unlike his contemporaries who turned to safe, fantastical depictions of the world, Rackham embraced the darkness, populating the familiar fairy-tale landscapes with goblins and mythical creatures.

Rackham’s personal life was closely intertwined with his art. He married a fellow artist, Edyth Starkie, who encouraged him to further experiment with watercolours. Their home became a creative haven where he continued to produce illustrations until his death in 1939, leaving behind over 3 300 works. Rackham received international acclaim, with exhibitions at the Louvre and gold medals awarded in Milan and Barcelona. His rare illustrated editions are prized among collectors of children’s books and illustration enthusiasts alike.

ON OUR SHELVES: ‘Little Brother and Little Sister’ (Grimm Brothers), ‘Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens’, ‘Mother Goose’

Beatrix Potter

Beatrix Potter’s (1866–1943) approach to illustration differs significantly from that of Rackham. Her passion for scientific observation and her ability to turn the peaceful countryside landscapes she visited as a child into backdrops for fantasy stories allowed her to bring life to a charming world where animals took centre stage.

Born into an upper-class Victorian household, Potter was educated by governesses and had limited contact with other children, finding companionship in animals and the natural world. Her childhood pets, including two beloved rabbits, Peter Piper and Benjamin Bouncer, became her earliest models and a lifelong source of inspiration for her stories.

Potter’s connection to the English countryside, especially the Lake District, deeply influenced her visual storytelling. Summers spent roaming its wild beauty filled her journals and sketchbooks with studies of flora and fauna, grounding her whimsical illustrations in the realism of field observation. Despite her parents’ support for her education, societal norms of the Victorian era limited Potter’s academic opportunities. However, this did not stop her from becoming an accomplished botanical illustrator, producing detailed studies of fungi that rivalled the work of professional scientists. Her precise line-work and naturalistic compositions, skills honed through her scientific drawings, later became signatures of her illustrations for her children’s books.

The spark of her literary and artistic legacy began humbly: in a letter to the children of a former governess, she sketched the tale of a mischievous rabbit named Peter. That letter would evolve into The Tale of Peter Rabbit, self-published in 1901 after multiple rejections from publishers. It was an instant success, and the tale, featuring animals in waistcoats and bonnets, became a landmark in Victorian children’s literature.

Potter was also a pioneer in character merchandising, recognising early the potential of her illustrations to leap from bookshelves to toy chests. As early as 1903, she patented a Peter Rabbit doll, making literary history as the first author to license a character and turning the book series into an international brand. Her hand-drawn world expanded into painting books, board games, figurines, and tea sets — each item preserving the charm of her original watercolours.

Though she is most famous for Peter Rabbit and his woodland companions, Potter’s legacy lies in the enduring visual language she created. She set a new standard for illustrated children’s books, and her work remains central to both literary history and the world of rare book collectors today.

ON OUR SHELVES: ‘The Tale of Little Pig Robinson’, ‘The Tale of Jemima Puddle Duck’, ‘The Tale of Mrs. Tittlemouse’

W. Heath Robinson

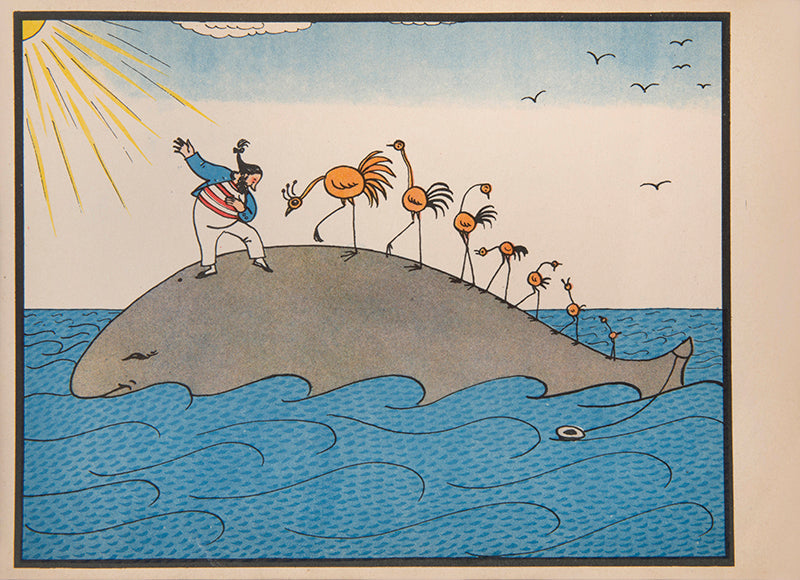

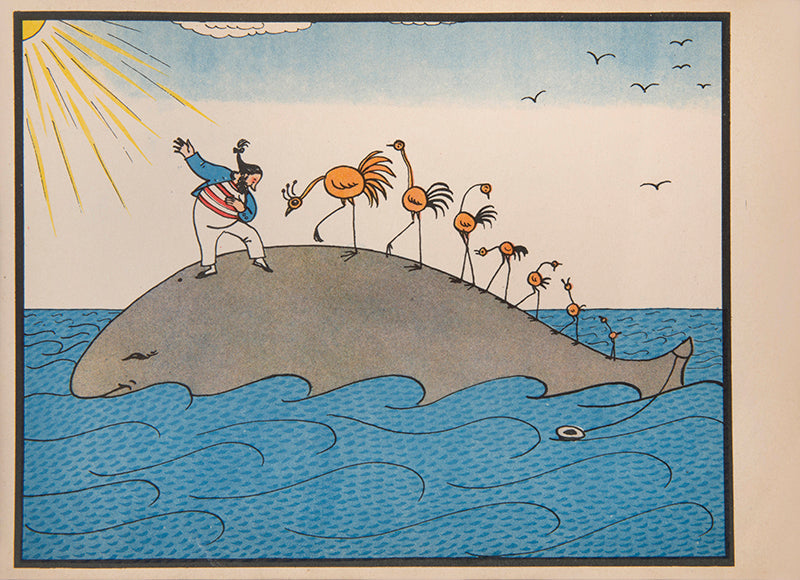

W. Heath Robinson (1872–1944) is arguably one of the most unusual children’s book illustrators on this list. His name even appears in the English dictionary, used as an adjective to describe overly elaborate, impractical contraptions — thanks to his instantly recognisable illustrations of fantastically complex machines built to perform the simplest of tasks.

Born into a family of artists in London, Robinson originally aspired to be a serious landscape painter but soon realised that illustrating books offered a more viable career path. After studying at Islington Art School and the Royal Academy, he began illustrating classic works such as Hans Christian Andersen’s Fairy Tales, quickly earning acclaim for his pen-and-ink technique. Robinson’s breakthrough came with Uncle Lubin, published in 1902, a children’s book he both wrote and illustrated, in which his playful sense of humour and penchant for the absurd first came to the forefront. His machines, drawn with intricate details and a wry sense of humour, delighted readers and brought comic relief during both World Wars, especially through magazine cartoons that lampooned the absurdities of modern life and the machinery of war.

Despite the challenges of changing artistic tastes and the hardships of wartime, Robinson’s artistic output remained consistently inventive and engaging. He produced thousands of illustrations for books, magazines, and advertisements, each showcasing his unique wit and technical skill. Today, Robinson’s illustrations are highly collectible and celebrated for their timeless charm and mechanical imagination.

ON OUR SHELVES: ‘Bill the Minder’, ‘Uncle Lubin’

Dr. Seuss

Theodore Seuss Geisel (1904–1991), best known by his pen name Dr. Seuss, began his career as a little-known editorial cartoonist in the 1920s. He would go on to become one of the most influential children’s book illustrators of all time, with over 600 million books sold worldwide, translated into more than 20 languages.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Dr. Seuss illustrated all his own books, ensuring his vision was fully realized on every page. He was particularly meticulous about colour, even developing specially numbered charts to achieve the precise saturated reds and blues found in The Cat’s Quizzer, chosen specifically to hold the attention of young readers. Dr. Seuss’s signature style is instantly recognisable: whimsical characters with rounded, droopy shapes, and fantastical buildings and machines that curve and twist with no straight lines in sight. From the mischievous Cat in the Hat to the scowling Grinch, his characters feel alive and animated.

Beyond children’s books, Dr. Seuss’s artistic talents extended to advertising and fine art, where his playful yet precise style continued to evolve. His work is sometimes classified as maximalism or postmodernism, reflecting its bright and joyful nature. Throughout his prolific career, he maintained a tone of ironic politeness and absurdity — qualities that helped turn his books into timeless classics.

ON OUR SHELVES: ‘The Cat’s Quizzer’, ‘On Beyond Zebra’, ‘Maybe You Should Fly a Jet!’

Maurice Sendak

Few illustrators have dared to explore the raw emotional landscape of childhood as honestly as Maurice Sendak (1928–2012). His ground-breaking artworks transformed the canon of children’s literature, opening the door to stories that were both wondrous and deeply unsettling.

Having grown up in Brooklyn with Polish-Jewish immigrant parents, Sendak was largely self-taught and began his career illustrating other authors’ works before emerging as a singular creative force in his own right. He illustrated over 100 books throughout his sixty-year career, collaborating with notable authors and reimagining classics. His illustrations broke away from the idyllic images that had long dominated children’s literature, instead offering worlds that were at once fantastical, unsettling, and deeply human.

Nowhere is this more evident than in his iconic work, Where the Wild Things Are (1963). A winner of the Caldecott Medal and the National Medal of Arts, the book remains a treasured classic that redefined what picture books could achieve. The lush, dark jungles and expressive characters reflect Sendak’s ability to capture the rawness of childhood emotions. He believed that illustrations should not just clarify the text but also mystify it, adding layers of meaning and ambiguity that encouraged children to confront their own feelings and fears. What sets Sendak apart is his refusal to condescend to young readers. He trusted children to engage with stories that explored fear, anger, and loneliness — an approach that was considered controversial at the time. His legacy has inspired generations of children’s book illustrators to embrace emotional honesty in their work.

Beyond his books, in the 1970s he began designing sets and costumes for operas and ballets, including Mozart’s The Magic Flute and Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker, bringing his distinctive visual storytelling to the stage. Sendak moved to Connecticut and lived there for many years, continuing with his writing and creating illustrations until his death in 2012. His legacy endures through the Maurice Sendak Foundation, which preserves and promotes his work. His illustrated books are treasured by collectors for their unique portrayal of childhood’s complexities that resonate across generations.

ON OUR SHELVES: ‘Where the Wild Things Are’

Explore the legacy.

If you are looking to grow your collection of children’s illustrated books or to simply revisit the classics, browse our current selection of rare and first editions online or in-store.